Hydrocolloids

The Invisible Architecture of Texture

There are ingredients that change the way we cook, and others, quieter and more elusive, that change the way we think about cooking.

Understanding this second kind of ingredient does more than give us a new lens for looking at the world. It becomes a tool of real precision, something that allows us to anticipate reactions, sense how matter will behave, and carry complex ideas onto the plate while preserving shapes and structures with an almost architectural precision.

Among all the ingredients that orbit our culinary universe, there is a family that appears constantly in our everyday life without us noticing it, or the importance it has gained in how we understand contemporary gastronomy.

If you are reading this in a café, take a moment to look around. A pastry in the display case might be shining beneath a soft glaze. The foam on your cappuccino holds its shape without collapsing. At the next table a gelatin trembles at the lightest touch of a spoon or a thick sauce settles on its surface as if gravity were something optional.

In all these ordinary, silent gestures, hydrocolloids are there, working unseen. They are discrete, invisible molecules operating at the intimate level of water physics, a territory we usually overlook when we think in culinary terms, yet one where much of the sensory pleasure of food is decided.

The most common view of cooking tends to reduce it to three basic gestures: applying heat, mixing ingredients, transforming flavors. But both contemporary gastronomy and many older culinary traditions that intuited this without naming it reveal a deeper dimension where many processes unfold simultaneously. Among them, one plays a particularly decisive role in the texture and sensory experience of a dish: the way we manage the behavior of water.

In the vast majority of foods, water is the medium in which their structure organizes itself. With the exception of a few purified or dehydrated ingredients such as oils, sugars, salts or dry powders like starches and gelatin, nearly everything we cook contains water in varying proportions. Recognizing this structural condition helps us understand why so many culinary transformations depend on aqueous systems, and how water’s behavior shapes the texture and sensory perception of a dish.

In the kitchen, water is not merely present, it acts. It carries heat, dissolves and transports compounds, facilitates flavor extraction, and enables the molecular interactions that transform matter. It gelatinizes starches, dissolves sugars and salts, absorbs aromas and nutrients, acts as the dispersion medium in colloidal systems, and is essential to stable emulsions when the right agents are involved. Practically speaking, it is the medium through which texture takes shape and sensory experience is articulated.

Understanding this structural role of water leads to a natural question. If so many culinary transformations depend on water’s behavior, is there a way to modulate it with intention, precision and consistency?

The answer leads us to a family of molecules that contemporary gastronomy has learned to look at with new eyes, even though they have accompanied many traditions for centuries.

In this scenario, hydrocolloids are molecules that interact intimately with water. They persuade it, slow it down, immobilize it, organize it into three-dimensional networks. They make water behave in ways it would never choose on its own. This is why understanding hydrocolloids is not simply learning to work with uncommon ingredients, it is learning a material grammar. A different way of reading what is happening in a cream, a sauce, a glaze or a purée. A way of illuminating processes that have always been there, working silently, but that we hadn’t known how to name.

What Is a Hydrocolloid?

To understand what a hydrocolloid is, it helps to look beyond its culinary reputation. Essentially, from a physicochemical perspective, a hydrocolloid is a hydrophilic macromolecule, a large, flexible molecule with a chain-like structure and affinity for water. That affinity is not a minor detail. It determines how it behaves and, with it, its culinary power.

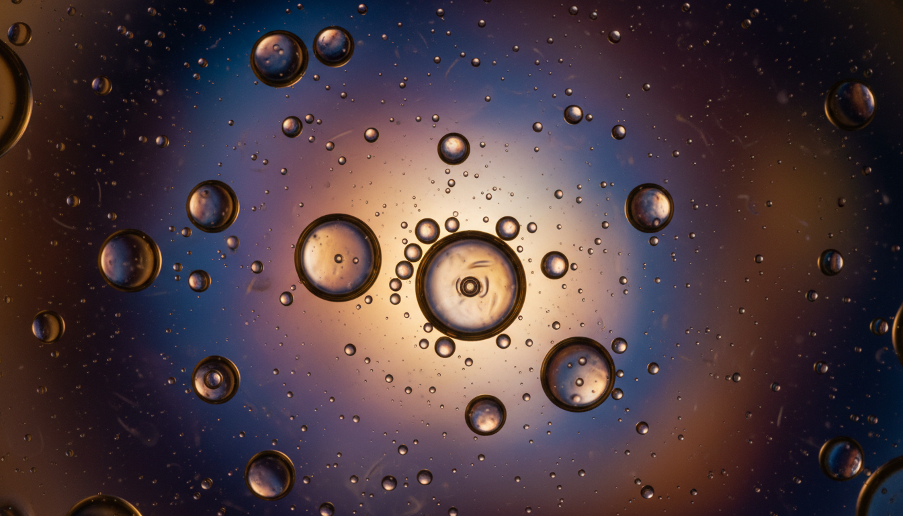

When a hydrocolloid disperses in a liquid, it interacts with it to create a colloidal system, which in simple terms is a mixture where tiny particles remain dispersed without dissolving and without separating.

They are not small enough to dissolve like sugar, nor large enough to sink like ground coffee.

In that intermediate territory, between the liquid and the structured, the textures of contemporary cuisine begin to emerge.

These macromolecules can hydrate and trap water, thicken it by slowing its movement, partially immobilize it to form a gel, or create hybrid systems such as more stable foams and emulsions. In rheological terms, they modify how a material flows, deforms or resists movement. And although the word may seem distant, rheology is present in the everyday gestures of cooking: the fluidity of a sauce falling in an unbroken thread, the elasticity of a gelatin trembling at the slightest touch, the sheen and controlled fall of a glaze.

Each of these expressions is at its core, a conversation between water and a hydrocolloid, a molecular balance that determines the final character of a dish.

A History Older Than Modern Gastronomy

We often think of hydrocolloids as a recent discovery, something born in laboratories, modernist kitchens and technical manuals. Having understood, isolated and classified them with such rigor can give the impression that they belong exclusively to the contemporary world. Yet for centuries they have lived in kitchens in diverse forms, generally intuitively and as part of deeply rooted gastronomic traditions where cultures worked with hydrocolloids without necessarily knowing they were doing so.

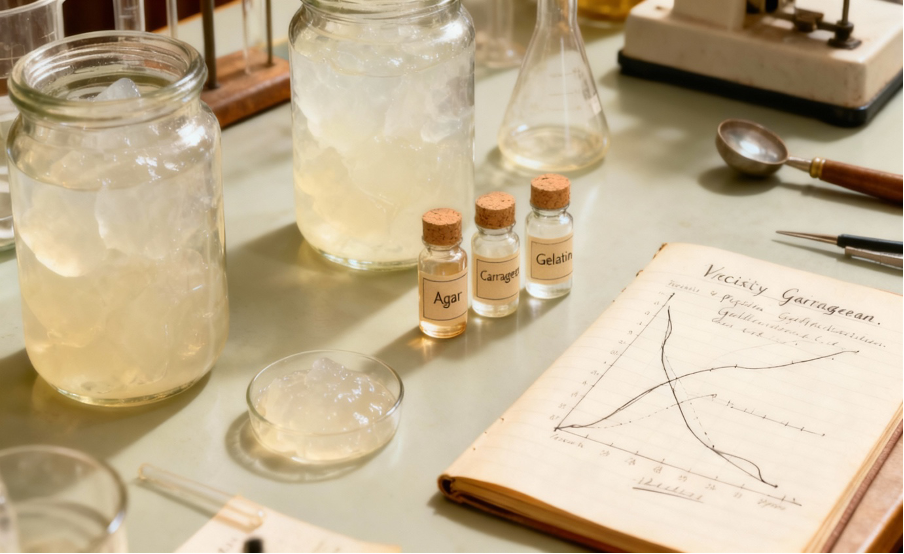

The gelatin that shaped colorful aspics in Europe, the agar used in Japan since the seventeenth century, the rice and wheat starches that thickened sauces in China, the plant mucilages that gave body to drinks and stews in the Middle East… all were familiar resources, but their logic remained hidden under intuition.

At the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries, organic chemistry and food science began a process of observation that transformed this landscape. In French, German and British laboratories, scientists studied the properties of gelatins, pectins and polysaccharides extracted from algae and seeds, seeking to understand how these substances interacted with water and modified texture.

Meanwhile, in Japan, something happened that, from today’s perspective, seems both unexpected and revealing. Agar, long used in their cuisine, began to be industrially standardized due to the rise of microbiology, which adopted it as an ideal culture medium for its stability, clarity and thermal behavior. Europe had known gelatins, mucilages and starches for centuries, but agar became the first hydrocolloid to arrive from Asia as a standardized industrial product, refined in the laboratory before being interpreted as a culinary ingredient. Science adopted it long before cuisine did.

Thus, while Europe advanced in the chemical characterization of traditional hydrocolloids, Japan contributed an ancestral gel that, transformed by scientific research, would return decades later to kitchens with a completely new meaning. Without anyone predicting it, culinary texture was beginning to take shape in a silent dialogue between gastronomy, industry and the laboratory, between ancestral practice and technical understanding.

The great transition occurred between 1930 and 1960, when the global food industry in Europe, the United States and Japan needed to stabilize products capable of traveling long distances and resisting time and temperature. This turned the study of hydrocolloids into a technical necessity. Carrageenans were isolated, fruit pectins purified, viscosity curves and gelation temperatures mapped, and the first classifications of gelling agents, thickeners and stabilizers were established. Traditional kitchens had always used them; science, for the first time, began to truly understand them.

This new scientific understanding began to influence cuisine. In Europe, a movement was emerging that would later become the prelude to the avant-garde: the Nouvelle Cuisine of the 1970s, especially between 1972 and 1978, which questioned traditional densities and sought lighter, more precise cooking. In that context, Michel Bras, whose work took shape from the mid-70s to the early 80s, developed a radically new sensitivity toward vegetal textures and natural juices. His gestures anticipated a path that, years later, would converge with the technical and scientific understanding already taking form. Cuisine was beginning to change, and science was becoming an extraordinary ally in that transformation.

Meanwhile, in Spain, the 1980s gave rise to the New Basque Cuisine. Juan Mari Arzak was not yet working with modern hydrocolloids or scientific frameworks, but he introduced a fundamental idea: that tradition, technique and creativity could coexist without conflict. His cuisine created the cultural ecosystem that would later allow Spain to become the world epicenter of culinary experimentation.

In this climate of transformation, by the late 1980s new questions began to emerge that traditional cuisine had never clearly formulated. What truly happens when a sauce emulsifies? Why do some proteins coagulate and others do not? How does water behave when it changes state? What invisible forces sustain a texture?

Physicist Nicholas Kurti and chemist Hervé This dedicated their research to observing these processes with the same curiosity with which cooks had intuited them for generations. Their purpose was not to establish a culinary style, nor to dictate a movement, but to create a language capable of describing culinary matter with rigor and illuminating transformations that had always been there, hidden inside a pot or within the structure of a gel.

To this study, which united physics, chemistry and cooking in a shared territory and transformed the way culinary matter was understood, Kurti and This gave a name that would mark a before and after in gastronomic history. In 1988, that territory received its name: Molecular Gastronomy.

By the mid-1990s, this new scientific perspective found its first interlocutor in haute cuisine. Pierre Gagnaire, at his restaurant in Paris, with an open sensibility and insatiable curiosity, was the first chef to actively engage with this conceptual framework. In his collaboration with Hervé This, an idea born in a laboratory acquired an unexpected life in the kitchen. Physics and chemistry ceased to be abstract fields of study and became expressive tools capable of extending the limits of culinary creativity.

In those same years, though following an independent path, Ferran Adrià transformed this knowledge into culinary language. At elBulli, hydrocolloids moved from being industrial or scientific tools to becoming expressive structures. Agar, xanthan gum, methylcellulose, pectins, alginates and carrageenans became grammar. For Adrià, texture was not an outcome, but an idea. His cuisine did more than reorganize the limits of technical creativity; it triggered a new gastronomic paradigm, a movement that would influence an entire generation of chefs worldwide.

ElBulli became a creative laboratory functioning as a global hub, hosting figures who would later transform entire regions: Gaggan Anand at Gaggan in Bangkok, René Redzepi at Noma in Copenhagen, Grant Achatz at Alinea in Chicago, Massimo Bottura at Osteria Francescana in Modena. Even chefs who never worked directly there, such as Dan Barber at Blue Hill at Stone Barns in New York, found in Adrià’s revolution an intellectual spark that reshaped their own approach to cuisine. What began as an experimental gesture became a global current, a shift in sensibility redefining how a dish is imagined, conceived and built.

In parallel, in the United Kingdom, Heston Blumenthal at The Fat Duck was exploring how physics, temperature and sensory perception shape experience. His work did not derive from Adrià or Gagnaire but conversed with both from another angle. Where one explored culinary language, the other explored the mind that receives it.

From this encounter between cooking and perception a fascinating field would later emerge, exploring into how we eat, feel and interpret a dish. For those wishing to explore this sensorial dimension more deeply, the book Gastrophysics by Charles Spence offers an illuminating perspective on how senses, context and the brain actively construct flavor.

All this trajectory, from the first scientific observations of the twentieth century to the culinary revolution that redefined texture, had consequences reaching far beyond haute cuisine or molecular gastronomy. The ideas born in laboratories, creative workshops and avant-garde restaurants also opened the way to a new relationship with plant-based matter.

Though not explicit, but rather a subterranean movement, the impact on plant-based cuisine was enormous. The industry and the kitchen found in hydrocolloids a technical infrastructure capable of reproducing, reimagining or even surpassing structures that once depended almost exclusively on animal ingredients. That impact deserves its own chapter. We will return to it later, to understand how this family of molecules quietly intervened in one of the most significant shifts in contemporary food culture.

The result of this convergence between science, cuisine and creative thinking was decisive. Thanks to the complementary perspectives of physicists, chemists and cooks, hydrocolloids ceased to be invisible substances and became a legible territory. The technical knowledge accumulated over decades made it possible to name them, isolate them, classify their behaviors and organize them into families, opening a chapter as disruptive as the one that inaugurated molecular gastronomy.

This effort to bring order to complexity had one of its great translators in Martin Lersch, whose book Texture remains essential reading for cooks seeking to understand this universe with clarity and depth. As a summary, we present the main families of hydrocolloids and the keys that explain their behavior in contemporary cuisine.

The Families of Hydrocolloids

There are many ways to classify hydrocolloids: by origin (animal, plant, microbial), by molecular structure, by response to pH, by thermal sensitivity, by ion affinity, or by how they modify viscosity at different concentrations. Each of these approaches reveals a different perspective on the same landscape.

To understand them from a culinary perspective and maintain continuity with the narrative we’ve built so far, it is especially illuminating to group them according to how they intervene in water’s behavior. Rheology allows us to observe the continuum that runs from barely modified liquids to firm gels, and to understand how each hydrocolloid transforms the flow, density or structure of the aqueous system in which it acts.

Classifying hydrocolloids is essentially observing how each molecule alters texture through its intimate dialogue with water. From those that barely modify its fluidity to those that immobilize it within solid networks, each family occupies a precise place along this spectrum. This journey organizes them from the most fluid to the most structured, allowing us to read culinary matter as a gradient of possibilities.

1. Hydrocolloids that gently modify fluidity

(Very low viscosity and no gel formation)Examples

• Gum arabic

• Ghatti gum

In the kitchen: light-bodied beverages, fluid glazes, airy emulsions with soft stability.

2. Stabilizing hydrocolloids

(Prevent separation, reduce syneresis and provide cohesion without thickening too much)Examples

• Guar gum

• Locust bean gum (LBG)

• Pectins in low doses

• Lambda carrageenan

Applications: smoother and more stable ice creams, beverages that do not sediment, sauces that stay unified and silky.

3. Thickening hydrocolloids

(Increase the viscosity of water without forming a gel)Examples

• Xanthan

• Native starches

• Modified starches

• Tara gum

In the kitchen: dense soups, sauces with gentle tension, purées that stay stable on the spoon, vinaigrettes that flow slowly and evenly.

4. Hybrid polysaccharides

(Can thicken or gel depending on concentration, pH, ions or temperature)Examples

• High-methoxyl and low-methoxyl pectins

• Kappa and iota carrageenan

• Functional modified starches

• Gum arabic in higher concentrations

In the kitchen: precisely set jams, glossy glazes, firm plant-based cheeses, structures that hold their shape without becoming rigid.

5. Gelling hydrocolloids

(Form three-dimensional networks that immobilize water)Examples

• Agar

• Gelatin

• Gellan, both high-acyl and low-acyl

• Alginate with calcium

• Kappa and iota carrageenan

In the kitchen: firm or elastic gels, spherifications, terrines and translucent gels.

How Hydrocolloids Work

If we had to condense their logic into three essential movements, it would be this:

Hydration

The macromolecules, long and flexible like chains, begin by absorbing water. They take it into their internal folds and pockets, wrapping it as if weaving an invisible film. The result is a liquid that becomes denser, more voluptuous, more tense from within.Thickening

As concentration increases, these long, flexible chains begin to interact and entangle. They brush past each other, intertwine in fleeting or persistent ways, and this contact reduces the freedom of water’s movement. The flow slows down. The texture gains body without yet becoming fixed.Gelation

When the chains encounter the right conditions (temperature, concentration, time or, in some cases, the presence of minerals such as calcium or potassium) they begin to connect. From these connections arises a three-dimensional network that immobilizes part of the water. What we call a gel is nothing more than this, water trapped in a molecular lattice.

The Impact of Temperature

Among all the variables that influence hydrocolloid behavior, temperature holds a decisive place. It can accelerate or slow hydration, modify viscosity, activate network formation or break it apart completely. In some systems, heat functions as a reversible switch; in others, it triggers a structure that does not go back. Understanding this difference is essential to reading what happens in a gel and anticipating its behavior on the plate.

Broadly speaking, we can distinguish two opposing logics in the relationship between temperature and gelation.

Thermoreversible Gels

They gel when cooled / They melt when heated.

They’re gels that live in a cycle, moving back and forth between states as if the matter were breathing.

Agar, gelatin and carrageenans belong to this category.

Their behavior allows creations that appear to defy intuition:

a glossy glaze that sets the moment it touches a cold dessert but becomes liquid again when warmed, or a broth that solidifies as it rests and melts on contact with heat.

Ionic or Non-Thermoreversible Gels

Once formed, they do not return to liquid when reheated.

They do not negotiate, they do not retreat.

This is where calcium-reactive alginates live, along with low-methoxyl pectins and other systems that depend more on ion chemistry than temperature.

From this logic arise:

. the spheres that hold their shape even in hot sauces,

. the jams that never revert to juice,

. the gels that endure cooking without disintegrating.

When we pause to look at hydrocolloids, we are not simply looking at ingredients. We are seeing the intimate architecture of cooking itself. In every gel, in every cream that finds its balance, in every foam that holds its shape over time, we glimpse the evidence that matter is not an obstacle but a terrain that can be observed, interpreted, cultivated and expanded. It is a terrain that inspires new generations of chefs and entrepreneurs to imagine forms of working with it that did not exist before.

Texture stops being an effect and becomes a form of understanding, a way of relating to the nature of water and to the forces that shape it.

To understand these materials is to recognize that cooking does more than transform ingredients. It transforms the way we perceive them. And once we learn how the invisible holds itself together, we gain a new way of imagining what once seemed impossible.

In the end, every preparation, from the simplest to the most ambitious, is a small treatise on the delicate balance between form, temperature, time and matter. And it is in that balance that cooking finds its capacity for discovery.

At The Black Artichoke, we will unfold this universe with the patience that any deep work requires. Over time, we will explore hydrocolloids one by one through recipes and processes that reveal how they work, why they behave the way they do and how they can become reliable allies for cooking with greater confidence and precision. If this path speaks to you, if you want to understand texture from within and expand your creative tools, I invite you to join us. You can subscribe to follow this journey and stay close to what comes next, an open and ongoing exploration of a territory with much to offer.

Biblography

Texture: A hydrocolloid recipe collection – Martin Lersch

Food Hydrocolloids – Stephen E. Harding

Modernist Cuisine: The Art and Science of Cooking Volumen 4: Ingredients and Preparations - Nathan Myhrvold

On Food and Cooking – Harold McGee

Molecular Gastronomy - Hervé This

A Day at elBulli – Ferran Adrià

Gastrophysics - Charles Spence